Agencies & Photojournalism

Let’s talk a little about how photojournalism has developed over the past fifty years. In the postwar period, there were only a few agencies in the world, and all reporting topics were mostly covered by American, and also by small German, English and French agencies. Many newspapers worked independently, hiring their own photographers. The most interesting situation was in England, which gave life to a completely unique style of work. British daily and weekly publications tended to work only with the best, most carefully selected photographers, “sending” them around the world. So, for example, Don McCullin appeared and a whole galaxy of agencies, such as Network, Katz Pictures, Camera Press, etc. appeared. A similar situation prevailed in the United States, the first country to correctly interpret copyright laws.

The first European photographers-freelancers were great romantics and very envied colleagues from the Anglo-Saxon part of the world, where the copyright rights were treated with respect.

Fortunately, in the late 1950s, a movement emerged spontaneously in Europe, uniting young photographers from different countries in an attempt to change the situation and establish new rules for the distribution of photos on the market. In the 60’s in the world of photojournalism, great changes took place, as a result of which the first basic rules of photo production and distribution were established, and the first attempt was made to cause respect for copyright.

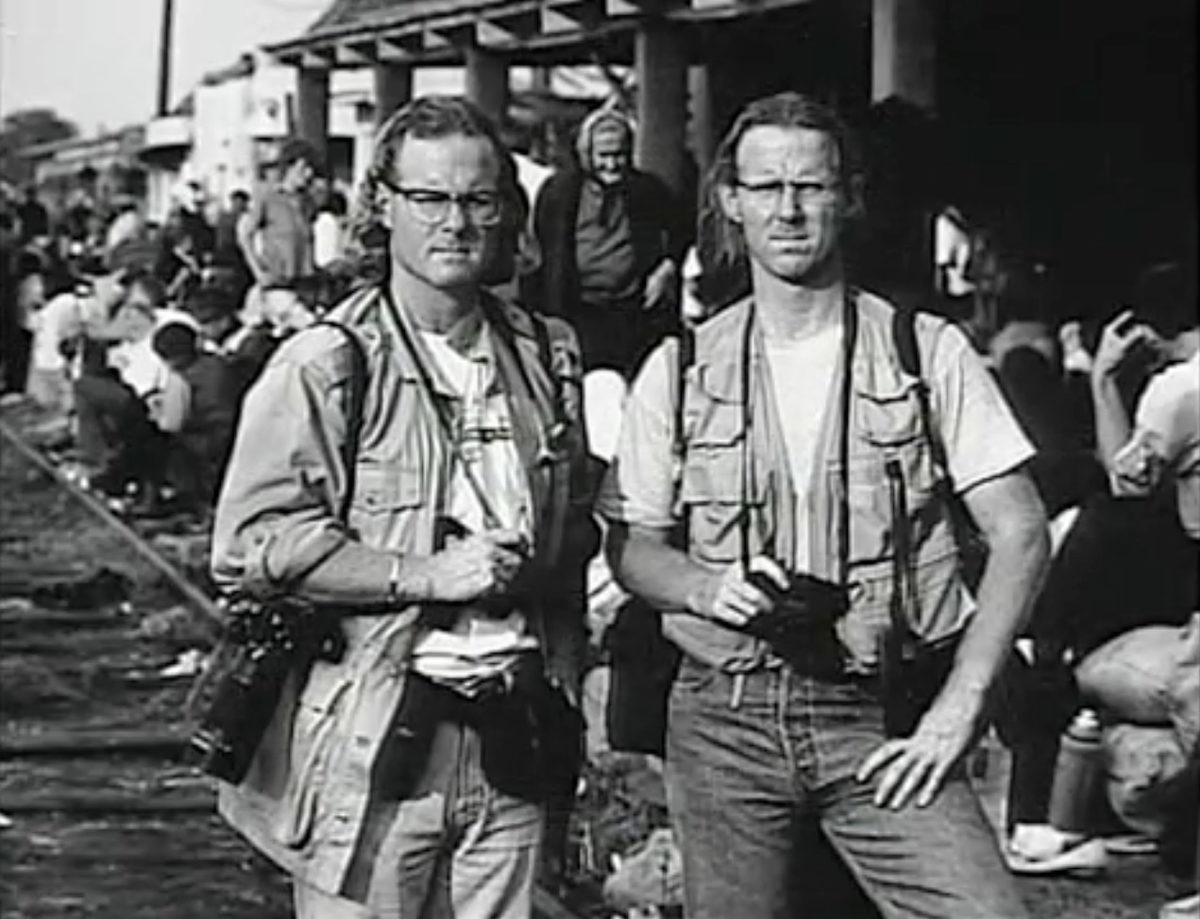

The political riots of the 60’s and 70’s helped photojournalism, forming a new layer of so-called concerned photographers. Such photographers of the agency were given the opportunity to travel around the world, shoot at the “hot spots” and capture the history. So they contributed to the birth of a real school of photojournalists working on the scale of the entire planet, which exists to this day. Large orders of such editions as Time, Life, National Geographic, Newsweek, German Geo, Sunday Times, New York Times Magazine became milestones in the history of photojournalism. It was her golden age: at the same time in different parts of the world worked such masters as Anthony Suau, Christopher Morris, James Nauchtwey, Turnley brothers, photographers of the French agencies Sygma, Gamma and Sipa, as well as photojournalists from the newly formed English agencies.

The idea of the formation of agencies Gamma and Sygma belongs to the French photographer Hubert Henrotte. He wanted to create a cost-effective production and distribution network, which, selling photo essays around the world, could cover costs and produce a high-quality photographic product. In my opinion, he was one of the best directors in the history of the existence of photo agencies. The success of the Gammas and Sigma created by Enroth is due to the emergence of other smaller, more specialized and narrowly focused agencies.

Until the beginning of the 1980s such a scheme of work was preserved and was justified, as it helped to create many important and truly serious works. Photographers were eager to cooperate with these agencies, providing them, for their part, publications in the best publications. They were all reluctant to enter into direct contact with the magazines, as the work in the agencies enabled them to travel and be free. Their places in newspapers and magazines were taken by art directors, photo editors and editors-in-chief, whose task it was to select “pictures”. The problem is that these people are not always able to adequately assess this or that material.

At this stage, there were two ways of understanding photojournalism.

The essence of American photojournalism, as it is defined in American universities and specialized educational institutions, such as the International Photography Center (ICP) in New York, is to serve as “historical evidence”. From this point of view, the depiction of the event is social, historical, or simply a reflection of our daily life, is meant to be a kind of “testimony” and should create for us a visual image of history. For this reason, “evidence”, it turns out, often carries the burden of ethical responsibility, and this load can be too heavy for those who choose for themselves the path of “a photographer who captures history.” Therefore, a very small number of military photographers manage to translate this rather utopian mission justify their work. Photography as a direct and dry documentation of the event makes it obvious the photographer’s ability to catch the very essence of the event. In this, the difference between the Anglo-Saxon way of thinking and what constitutes the grain of European photography, which tends to reflect history is not so straightforward. This difference is reflected in the language itself. Anglo-Saxons are more synthetic by nature: to express the same idea they will need only a few words of a sonnet, and a Frenchman or an Italian on the same subject will write a verbose poem.